Imperfect Rights

One aspect of Grotius I've been working on actively is the concept of an 'imperfect right' - how it functions, first of all, in Grotius' system, but also how it might be treated as a source for the rights-centric culture of modern liberal politics. I've been exploring this theme over the past year or so in papers I've presented before various audiences in philosophy, law, and political science (as well as in some of my teaching). I'll give it a try here as well - it will be a useful exercise for me to work out my thinking.

Basically, my working thesis is this: The early modern concept of an 'imperfect right' is what made possible the modern transformation of rights, from a technical lawyerly matter regarding remedies (that is, lawsuits), to the more familiar modern notion of rights as moral demands asserted against others. Imperfect rights aren't really rights - they're merely a heuristic, the correlative for 'loose' or thin moral duties that are described as being, in Latin, laxé or laté. At some point, however, imperfect rights become more than just a heuristic tool for legal theorists, but genuine rights that one can demand of others.

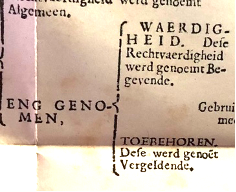

This category of 'imperfect right' is what makes possible a modern antagonistic liberal political culture that prioritizes the question whether there is a right to [fill in the blank]. In recent theoretical scholarship, this ever-expanding list of rights has extended to asking whether there is a right to territory, a right to secede, a right to exclude foreigners, a right to a guaranteed income, a right to asylum, even a right to sex! This is continuous with the early modern project of imperfect rights which begins by asking whether one can have something like a 'right' to benefit from another's generosity, kindness, or gratitude. Can one, in principle, have something like a 'right' to someone else's kindness or gratitude [or fill in the blank with your favorite virtue]? Yes, but only if one is 'worthy' [waardig; aptus] of it. It is a claim of merit or desert, what you deserve, rather than what you can demand.

By linking together the language of rights with claims of merit, Grotius - most likely, unintentionally (I don't believe Grotius really should be considered a 'liberal' in the modern sense) - plays a starring role in this transformation, with his concept of the 'imperfect right' - or, rather (more precisely), a 'less-perfect right' - because this would become a standard part of the vocabulary in the law and ethics of the Enlightenment.

Perfect right

But before going into those details, we need to know first what a 'perfect right' is, and how it differs from an 'imperfect right.'

The concept of a perfect right isn't really that difficult. Very simply, it's an actionable right - a right that you can demand and sue for in court to enforce performance of some act (e.g., repayment of a loan) that is strictly due (Grotius often uses the phrase - stricte debitum) to you. Grotius explains that this even as a matter of justice, but it might be easier to think of it in terms of injustice: When your debtor fails to repay a loan that is due to you, you've suffered an injustice. The debtor has failed in performing a duty and unjustly wronged you, as creditor. The purpose of your (perfect) right is to right that wrong, the injustice, you've suffered by the debtor's non-performance.

For such a vital concept to his whole system, Grotius' presentation was actually pretty clumsy and, consequently, left it to others (most notably Pufendorf) to really explain what makes a right 'perfect' and 'imperfect.' It appears in a passage in the opening chapter of De Jure Belli ac Pacis:

|

| Grotius, De Jure Belli ac Pacis I, 1, §4. Photo: Daniel Lee, 2023. |

This is the same excerpt from an earlier post, where Grotius conceptualizes jus in relational terms, as a Hohfeldian claim-right, A's claim on B's duty to perform (or forbear) the performance of some act. Grotius, of course, is writing three centuries before Hohfeld and doesn't use the modern vocabulary of 'claims.' Instead, he labels this, using a specialized Scholastic vocabulary, as qualitas moralis personae - the 'moral quality of a person.'

It is in this passage where he identifies the two main forms which a jus may take, which can be either 'perfect' [qualitas moralis perfecta] or 'less perfect' [minus perfecta]. It's worth noting that 'perfecta' in Latin is not an adjective, but a verbal participle from the verb, 'perficere' = to complete or to execute (as in a commercial transaction). My guess is that Grotius was probably thinking of the Roman law of sale, which identified an executed contract of sale as a venditio perfecta. (in a separate paper, I found some evidence for this connection in the influential legal humanist, Donellus, who taught at Leiden) There is an analogy at work: Just as a sale is 'completed' [perfecta] when buyers and sellers agree on a price, so too a right can be said to be 'completed' [perfectum] when an obligee successfully enforces an obligor to perform an outstanding obligation that is strictly due.

Imperfect right

If a perfect right is an actionable right that one can demand and, in principle, sue for in court, an imperfect right, by contrast, is an unactionable right - one cannot sue for enforcement, even if one's claim over another is meritorious. Like perfect right, imperfect right arises when there is some injustice - a moral failure to perform some duty.

But the sort of duties involved in imperfect rights concern, not legal duties (like the duty to repay a loan to a creditor or to return property to an owner), but duties of humanity - what Cicero once called officia, such as the duty of gratitude:

'In many cases it happens that an obligation binds us, while there is no correlative right in another party; just as it appears in the duty of having mercy and in the duty of showing gratitude.'

|

| Cicero, De Officiis (Amsterdam, I. Blaeu, 1688), I, §15 (47): 'No duty is more necessary than showing one's gratitude.' |

Gratitude is an especially interesting duty, because, in classical Roman law, it was actually actionable in a very specific case - in the relations between patrons and clients. Ingratitude by the client makes them liable to suit, the Actio Ingrati (or Revocatio in Servitutem) by which the freedman may be re-enslaved. (Apparently, the Louisiana Civil Code has retained this legal attempt to regulate gratitude in the law governing donations - the donee's ingratitude empowers the donor to revoke a donation).

But even in the sixteenth century, it was recognized that gratitude was generally unactionable, as Grotius acknowledges here:

|

| Grotius, De Jure Belli ac Pacis p. 221, II, 11, §3 on promissory obligations. |

'In many cases it happens that an obligation binds us, while there is no correlative right in another party; just as it appears in the duty of having mercy and in the duty of showing gratitude.'

So what about duties like gratitude? Is it obligatory (in the same way that it is obligatory to repay a loan)? Can someone else demand that we show gratitude? Some preliminary sketches:

1. Yes, such duties, like gratitude, are obligatory, but not because the law requires it (unless of course you were a freed client living under Roman law - or Louisiana). They are obligatory because natural law requires it. And why does natural law - right reason - require it? Well, just imagine what a world would look like where no one shows gratitude anymore. Could an orderly 'society' even be possible? There seems to have been real doubt about this. Society is not possible where everyone chooses to act like a selfish jerk (even if this may be the rational choice, given the options).

2. Can someone else demand that we show gratitude (or some other virtue)? In principle, yes - but only if they deserve it. To illustrate this point, I usually like to use the example of tipping in Western cultures (this example won't work in parts of the world where tipping is regarded dishonorable or offensive). Joel Feinberg usefully illustrates his vision of a world without rights - Nowheresville - as well.

Suppose you go to a nice restaurant (or, say, a coffee bar), and you are the beneficiary of extraordinary service from your server or barista. The server is surely deserving of your gratitude which customarily is expressed in a pecuniary gratuity, a tip, that reflects the service you received. But say you fail to leave a tip - or, say, you left a very meager tip. Would you have wronged your server? After all, tips are, by their nature, never strictly due. But they remain, in some sense, still obligatory, especially if they earned it and are deserving of it.

The discussions I've had with my students over the years have been very revealing. Sometimes, there is real discomfort and opposition to the suggestion that servers and baristas have a 'right' to be tipped. It crosses over a line, they say, and is an abuse of the concept of right. Others point to the structural inequities of modern service economies that make such workers' rights essential for survival, and the duty falls on consumers in this economy.

Every time you are asked to leave a tip, you are facing the Grotian concept of an imperfect right. You are, in essence, being asked whether your server, your barista, your driver, etc., has 'merited' and is deserving of your gratitude and, thus, has an imperfect right to it. But the reason why this can become so challenging is that there's an additional element of proportionality involved. So, when consumers deliberate, 15%, 20%, 25%, maybe something else, you are being asked to decide, not only whether to leave a tip, but also on what is a just reward that proportionally 'fits' with the service you've received.

This is why, in a critical passage, Grotius describes imperfect right as a concept of 'fittingness' or aptitudo:

|

| Grotius I, 1, §7 |

|

| Barbeyrac on Grotius I, 1, §7, where the term 'droit imparfait' is introduced for the first time. |

Your duty to show gratitude must proportionally 'fit' your server's effort - or even 'worthiness' or 'merit' or 'deservingness' for such a reward. Note that this is a different concept of justice involved than in perfect rights.

|

| Grotius III, 13, §4 |

You can be a person of low moral character - here, in Grotius' example, the stingy creditor - and yet still be fully entitled to your perfect rights. The stingy cruel creditor is well within his rights to sue his penniless debtor, so there is no question of proportionality here. The stingy creditor may not deserve it, but he sure can demand repayment in full.

Worthiness and unworthiness

One last point before I finish this post. Imperfect rights are based on claims of merit or worthiness. You have, in principle, a right to what you are worthy of - such as a good tip, if you deserve it.

What if you're unworthy of such benefits and rewards? Have you suddenly lost your rights? One of the most interesting aspects of Grotius' moral reasoning is the place of charity. Sometimes, you ought to do good for others, not because the other party is deserving or worthy of your kindness, but simply out of charity. There is a Christian theology in the background here that ultimately traces back to Grotius' use of Christ's New Commandment - to love each other. In this ethic of charity, rights become nugatory.