Grotius: Proto-Hohfeldian? Part 2

In my previous post, I showed how Grotius defined jus as 'that which was not unlawful' [= quod injustum non est]. This was simply Grotius' version of what Hohfeld would later call a 'privilege' or a 'liberty-right.'

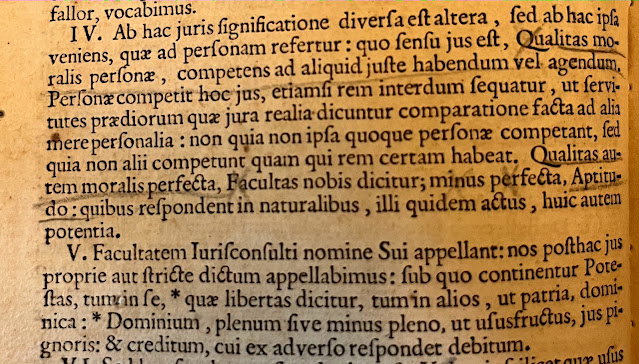

But this was not the only way to conceptualize jus, as he explains later in the opening chapter:

|

| Grotius, De Jure Belli ac Pacis (1646) p. 2, I, 1, §§4-5. Photo: Daniel Lee, 2023. |

Jus is a 'moral quality of a person enabling him to have or do something lawfully [juste].' There's a lot going on in this famous excerpt, but I think probably the most important point to stress is in the examples Grotius uses to illustrate. Jus functions as a relational concept - it is something that arises from legal relations between persons.

What kind of relations? The one he provides is 'dominium' (property ownership). When you own property (or if you have even a proprietary interest that is somehow less than ownership (this is what the 'minus pleno' means), like a usufructuary, your ownership positions you against everyone else in the world - that is, the non-owners of the property. This way of thinking about ownership as a right against the whole world was a fairly new way of thinking about property in Grotius' time. In this passage, he uses the phrase, jura realia ('real rights') that only started to be used in sixteenth-century jurisprudence. The legal relation here, then, is the relation between owners and non-owners, where only the owner has jus against everyone else not to trespass on property.

The other is that of debt. Creditors and debtors are locked in a legal relationship of obligation, whereby the latter are duty-bound to perform for the former. Again, there is a relationship of rights: The creditor has a legal right, a jus personalia, technically actionable against the debtor. Grotius even describes the position of credit and debit in terms of correlativity: One corresponds or 'answers' [respondet] to the other.

Both of these examples are drawn from the classical distinction between the structure of in rem and in personam suits in Roman law. But in this context, Grotius is among that generation of jurists 'experimenting' with the possibilities of detaching actionable remedies from rights, an achievement that would be acknowledged in later Roman-Dutch law.

|

| Arnold Vinnius, Institutionum Imperliaium Commentarius (Amsterdam: Elzevir, 1665) p. 22 on Inst. 1.2.12. Photo: Daniel Lee, 2023. |

What's the point? The point is this: Unlike 'liberty-rights' which arise in the absence of duty (when an act is not-unlawful), these rights essentially involve correlative relations of rights and duties. To wit: My right entails someone else's duty. The owner's right entails the non-owner's duty. The creditor's right entails the debtor's duty. And so on. To have a right means someone else must somehow be burdened under a duty owed to you.

But this raises another problem, one that has been a major puzzle that I am now actively trying to pursue in The Science of Right. While some duties may be moral duties (and thus, unenforceable), other duties are enforceable in court as legal duties. This is an old problem, reaching back to the classical ethics of Cicero and Seneca, and reconfigured in the deontological ethics of Kant. But its modern version really begins, in my view, in the crisis created by Reformed theology.

Grotius, emerging from a Reformed background, had a different way to label this distinction between strict and loose duties. While 'loose' [= laxius] moral duties he sometimes called officium, the enforceable legal duties in court, he described as 'strictly due' [= stricte debitum], such as the repayment of a loan or return of property to its rightful owner. The distinction pops up frequently throughout his writings, such as in this place:

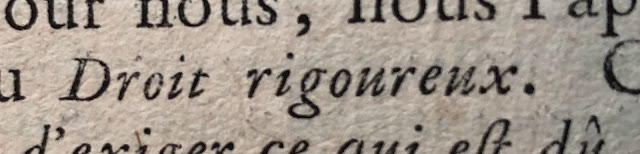

The right to demand performance of such 'strict' duties is what Grotius called jus stricte dictum, 'a right strictly so called.' Barbeyrac translated this same term into French as:

|

| Barbeyrac's Grotius, Droit de la guerre at I, 1, §5. Photo: Daniel Lee, 2022. |

This would later be called a 'perfect right' because it is a right that can be 'completed' or fully 'carried out' [= perfecta, such as in a venditio perfecta - a 'perfect' or 'completed sale' - in the Roman law of obligations].

Here then is another Hohfeldian moment in Grotius. Rights can take the form of 'claims' the one party may make and even demand of another. Hohfeld simply called these rights 'claims' or 'claim-rights.' Grotius, thus, worked out one of the basic distinctions (liberty-rights vs. claim-rights) in the Hohfeldian system almost three centuries in advance of Hohfeld. There's even more, but I'll discuss that later in the book itself.

There is one thought I need to highlight. Grotius recognizes that duties, while valid, may take different shapes and may bind in different degrees. A strict legal duty that is enforceable by a law court will have a different effect from a loose duty of humanity or of virtue that may bind on the basis of reason only - we may have a duty to show gratitude or kindness or some other form of benignitas - as classical jurisconsults often put it . And since duties may, it seems, correlate with rights of other parties who theoretically may demand performance of such duties, are there similar corresponding strict and loose rights? The answer, I believe, is yes. Or, at least for Grotius. And his analysis will have huge consequences for Pufendorf, Kant, and others who acknowledged the different degrees of duties - not to mention modern theorists of rights such as Gewirth and Dworkin.