Condignity and Congruity

It looks like I will need to take the leap into moral theology after all. I can't connect all the dots yet, at least not as clearly as I'd like (I don't even know which 'dots' I want to focus on yet). But the old Scholastic theological debate on condignity and congruity offers at least some family resemblances to the juridical form that Grotius will later provide, so it is probably a worthwhile area for some research. It seems Thomas, Scotus, and Henry of Ghent will be the points of entry. Any other suggestions?

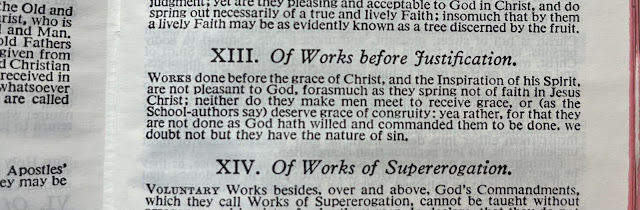

What does this have to do with rights? The theologians' unsettling question may go like this: Can you demand of God the divine rewards of heaven? Do you have a 'right' to enter heaven, based on your merits? For the Reformers, this couldn't be correct - it's too transactional; it burdens God with obligations and potentially even exposes God to the sin of Acceptio Personarum, i.e., failing to reward the worthy (as corrupt princes do when they reward offices and benefices to their unworthy cronies) according to distributive justice. Thus, this whole Scholastic tradition becomes suspect and even directly targeted in Reformation theology - e.g.:

|

| Article XIII, The Articles of Religion, Book of Common Prayer |

You may not have a strict right - but you could at least, in principle, view yourself, with the benefit of divine grace, as being worthy of divine rewards; just as the donor of a gift, acting out of liberality, is worthy of a return of gratitude. Worthiness of this sort is not a claim of right, but something kind of close to it.

Now here's another question: How much of modern liberalism is a secularized form of Scholastic 'congruitas' proceeding ex aequitate? I suspect it is a great deal.