Benignity

A note for Berkeley students: First, a local announcement for Berkeley students. For spring 2024, I can now say that I will be offering a new lecture course, "Jurisprudence: A Classical Approach to Legal Science." This will now become a regular part of my course offerings for undergraduates at Berkeley. It will introduce the subject of Jurisprudence in the "old-fashioned" way, by inviting students to study real cases in Roman law and reflect on the conceptual puzzles that emerge from what is the most important legal system in history. We will then trace the modern history and major problems in jurisprudence, focusing especially on Grotius, Austin, and Hart. Unfortunately, students who have already enrolled in my Roman law courses in the past cannot enroll in this course, since much of the material will be the same - sorry. It might be possible for graduate students to audit - however, I will be offering a seminar on Natural Law in early modern political thought (as a 212B course) as well in the spring - or at least, that is the plan now.

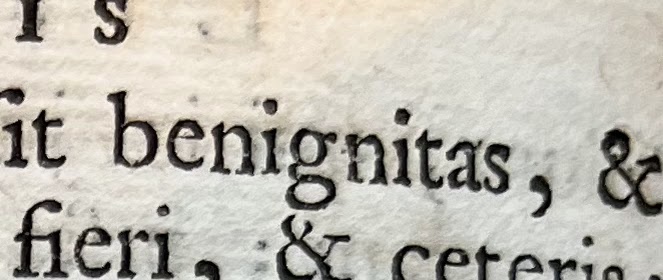

Last week, my undergraduates and I read in seminar an excerpt from Cicero De Officiis. It had been a while since I really read that text closely. But I found it very useful for making some sense of later authorities, and now I'm wondering if students too should spend more time with De Officiis as a preliminary before diving into Grotius. Let me share a couple that have been on my mind: One is the notion of 'benignity' - or kindness (the following images are from a 1688 print of De Officiis I acquired several years ago):

Or, variously, 'beneficence' and 'liberality':

The concept of benignity appears in conjunction with Cicero's discussion of justice. Both are duties (or 'officia'), which he thinks are necessary to maintain the bonds holding together human society, an idea of central importance for the natural-law concept of 'sociability.'

So: Not only must we be just to each other, we must be kind or 'benign' to each other in our dealings. And not only must we be kind - as a general principle, according to Cicero, our benignity must be 'pro dignitate' - in proportion to the worthiness [= dignitas] of the other beneficiary of our benignity:

Consider, then, Cicero's treatment of reciprocity, or 'requiting,' of kindnesses and gifts.

'No duty is more necessary than returning a kindness.' It is, in fact, obligatory to requite a kindness (an example I suggested to my students was the unwritten rule of the bar: if one buys the first round, you really must buy the second round - that's how you keep friends - or, to use Cicero's language, maintain the bonds of humanity).A number of my insightful students observed the transactional nature of gifts and favors emerging from these passages - anticipating some of the themes in Marcel Mauss's classic study on the gift.

Such duty of benignity and its application beyond the strict requirement of the law is reflected in Roman law (one example is at D.39.5.25). This is one area I have more I want to say on for a later post.

Even the so-called duties of humanity (officia humanitatis) make an original, or at least early, appearance in De Officiis at this point:

One common example that pops up again in Grotius and Pufendorf is the right to access aqua profluens (running water). Deny no one water access if it costs you nothing. The Digest will later record this as a basic law of nature (D.1.8.2.).

With so many duties that we need to keep track of, Cicero ends this discussion with what I felt was an ominously modern vision of modern life: Everybody becomes a 'calculator of duties':

Who owes what, to whom? The more people think like that, it's only natural that people begin to ask also, who has the right to expect what another owes? Cicero wasn't ready to ask that question so boldly. But his early modern readers were.