The history of jurisprudence

The history of jurisprudence, in Anglo-American legal philosophy scholarship, is basically Aristotle, Aquinas, Hobbes, Bentham, and Austin. Occasionally, maybe Grotius and Kant, but that is usually about it. (I can think of at least one relatively recent article that tries to look at Bodin's legal theory. See Chapter 4 of The Right of Sovereignty for what was wrong with that study).

This is really unfortunate, for several reasons. Legal philosophy tends to have a simplistic picture of how modern legal ideas develop. In terms of methodology in the study of the history of ideas, they are still stuck in the 1960s. Perhaps that's unfair, but years of peer-reviewing papers and book proposals and attending seminars only confirms my view that the reason why legal philosophy has not progressed all that much as a field is because they don't know their disciplinary and intellectual history and seems ignorant that some of the problems legal theorists investigate have a venerable background.

It's also unfortunate that, by privileging five or so sources (most of whom weren't even lawyers!), so many interesting sources have been overlooked and condemned to obscurity. This has been changing slowly in recent years with the excellent work of legal historians with interests in theoretical and philosophical problems.

One of the sources I've become very interested in recent years is this:

|

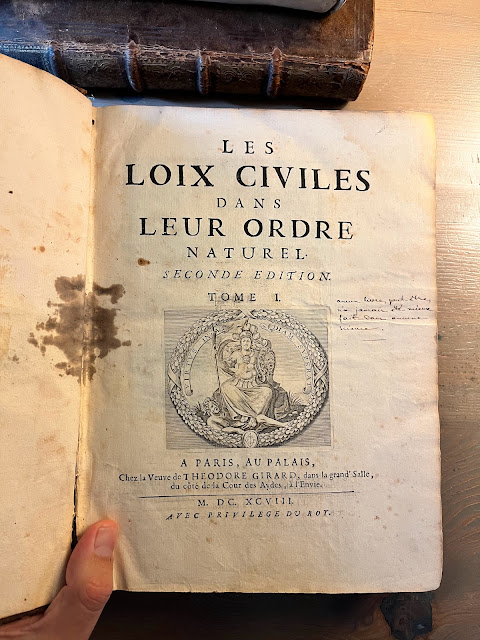

| Jean Domat, Les Loix Civiles dans Ordre Naturel (Paris, 1698). Photo: Daniel Lee, 2023. |

There are a number of reasons why I'm interested in this text - it is a product of a creative intellectual movement in jurisprudence away from the more old-fashioned jurisprudence that relied heavily on the traditional teaching of Roman law, but without doing away entirely with its substance; it envisioned law for a French society governed under an absolute monarchy.

But it is the opening section of the work that ought to attract attention of theorists:

A treatise on laws that should be treated as a 'classic' seventeenth-century statement on the origin, force, and limits of legality. This will likely be one of the major sources I'll want to spend some time with in The Science of Right - although it's too early to tell just yet what exactly I want to say. The only I can say for sure right now is that it's a very creative text - far more interesting, in my opinion, than some others that are still considered required reading in philosophy of law seminars around the world.