Maxime du droit civil

The academic year is almost over, as I finish up grading papers for this term. I'm now already starting to plan my teaching for the summer and next year. I will be offering again my 112B - Berkeley's History of Early Modern Political Thought course - and I've started the process of ordering textbooks. I am rethinking some of the textbook choices I've made in the past for this course.

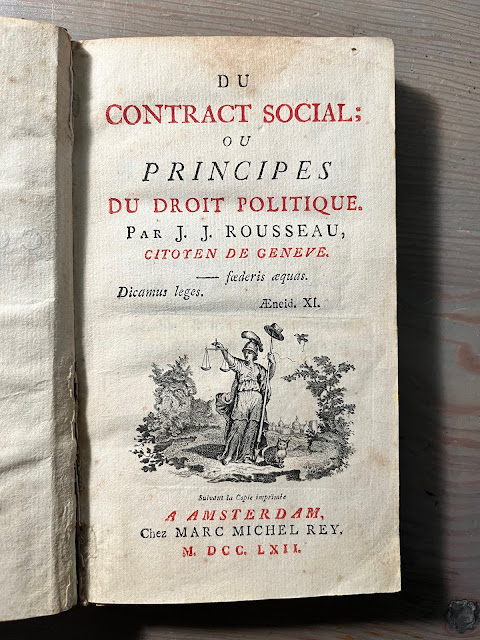

Rousseau is one example. In the past, I've assigned the Cambridge edition. I can no longer do so. There are serious flaws in the translation concerning the French term, droit. This might seem like a petty point, but it actually is a big deal for me because it is arguably the central concept in the whole of the Social Contract which, it's worth remembering, is a work on principes du droit politique.

Droit is a central concept in this work. English translations often render it as 'right.'

Consider the passage:

|

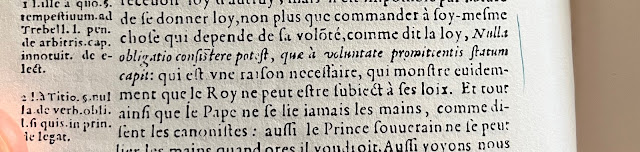

| D.45.1.108.1 = l.A Titio.§Nulla promissio.ff.De.verb.obl . |

This is a famous passage in the Digestum Novum of Roman law in the title concerning verbal obligations - stipulations. The principle stated here becomes important in the intellectual history of sovereignty because it raises the question whether sovereigns (who are, by definition, legibus soluti - i.e., not bound by their laws) could nevertheless be bound by their contracts. Bodin would cite this maxim in the République.

|

| Bodin, République 1583: 132. |

But one particular species of contract can never be binding: A contract, or promise, due to oneself. That is what this maxim addresses: 'No promise can be made that rests on the will of the promissory.'

This presents a special problem for theorists of popular sovereignty. If 'the people' are both sovereign and subject, this legal maxim nullifies the force of any reciprocal obligation between sovereign and subject in a democracy. To whom do citizens owe their political obligations? A standard traditional answer is their sovereign. But, as Rousseau just explained, the people are the sovereign. Hence, the problem: Can the people be obliged to themselves?

Rousseau's solution, of course, is what leads him to formulate the concept of a general will, as distinct from any particular private will or even the aggregate will of all.

This is just one example of many where careless translation choices fail to convey a very simple, straightforward idea and has, consequently, done real damage to a generation of students in political theory. This is why, as I always advise my students, it is vital to consult the original sources: Translations are never original sources.