Appetitus societatis: Natural sociability and natural law

|

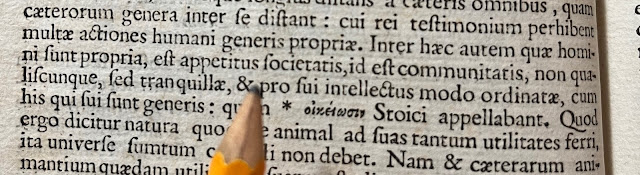

| Grotius, De Jure Belli ac Pacis: Prolegomena fol.4*vo. |

This famous passage appears on the second page of the Prolegomena of Grotius - roughly, 'Among those characteristics that are specific to humans is the desire for fellowship - appetitus societatis - that is, for kinship [communitatis] - and one, not of any and every sort, but of the peaceful kind, and ordered according to the measure of his understanding, with those who are of his own kind - a characteristic which the Stoics called 'sociableness' [οἰκείωσις].

We are naturally hardwired to seek the company and aid of others. This is the axiomatic starting point for Grotius' theory of natural law. Humans are fundamentally other-regarding creatures. And from this quality of sociableness or sociability arises law. This quality of sociableness is, as he puts it, 'the fountain of its law'

|

| Grotius, De Jure Belli ac Pacis: Prolegomena fol.4*vo. Fons ejus juris was translated into English by Morrice as 'Fountain of Right,' another poor translation choice for such a crucial sentence. |

Partly my worry is that this argument involves a kind of naturalistic fallacy: Humans are naturally sociable; therefore, humans are naturally obliged to be sociable. Something seems to be missing.

I have wondered what is the 'sequence' that Grotius must have had in mind in the chronology that leads from sociability to law. And I think it goes something like this (or at least this is how I understand it right now): Humans are naturally sociable. We help each other out. We care for each other and show kindnesses to each other. We do favors for each other. We give gifts to each other. Over time, an expectation of reciprocity results in an informal economy of favors and gifts: I scratch your back, you scratch mine.

When everybody is sociable towards each other, the benefits of such social cooperation are enjoyed by everyone and, in principle, should be manifest to all beneficiaries. 'Natural law' seems to emerge as precepts of rationality: If our goal is keep these benefits of sociability, what must we all do (or must not do)?

Natural law, on this reading, emerges partly as a moral anthropology and partly as a consequentialist argument. (There is even, I think, some family resemblance from how I'm interpreting the evolution of natural law from sociability and the so-called 'fair-play' theory of obligation: both rely on the intuition that beneficiaries of social cooperation have some duties to maintain that cooperation).

There's nothing especially or intrinsically valuable, let alone 'sacred', about the specific precepts of natural law. These are simply the basic rules that everyone must comply with to maintain favor with others, and to maintain the social bonds of fellowship so that we will all want to continue giving aid and showing kindnesses to each other. It's no coincidence, I think, that some of the natural law precepts almost sound like rules of etiquette - e.g., gratitude. Ingratitude is a grave moral failure - why? It's not because it is somehow an offense to God. Rather, it is an argument belonging to social theory. Nothing will dissolve the bonds of society as fast as ingratitude.

What Grotius calls 'natural law' thus emerges or evolves from our sociable quality. They are social norms, which can be justified as rational (or, rather, 'in accordance with reason') because compliance with them only ensures that we continue to enjoy the benefits of sociability.

But this can't be the whole story. Natural laws are 'laws' - and the definitive characteristic of laws is that they are obligatory, not just rational. There is a gap, then, between social norms and obligatory laws, and bridging this gap is one of the challenges I'm facing. But both pieces are necessary. It's vital for Grotius to press on the obligatory aspect of natural law for one crucial reason. Humans may be naturally sociable - but such sociable conduct isn't guaranteed. Grotius hasn't escaped the challenge of prisoner's dilemma selfishness.