Sources

In recent years, I've started collecting original sources related to my research and started building up a library of antiquarian books in early modern law. I started doing this three years ago during the COVID pandemic, largely out of necessity. Rare books libraries I've used (such as the Robbins Collection in Civil and Canon Law at Berkeley) were closed, and my poor eyes couldn't handle spending hours staring at Google books.

I now regularly teach using original sources in my lectures and seminars. Especially for undergraduates, the experience of handling an original text that is 500 years old can be a transformative one and simply cannot be substituted by reproducing a digital image on a slide. So I invite my students, when I teach Bodin, Grotius, or Hobbes, to hold and read from an original source text - in part to reinforce the materiality of ideas.

But I'm also driven by a sense of urgency in using original sources. I've found many modern translations pretty unreliable (and which, in turn, results in unreliable scholarship). This is particularly a problem in historical scholarship on rights. That is because the word for 'rights' in Continental European legal languages (jus, droit, diritto, derecho, Recht, etc.) also means (and more likely means) 'law.'

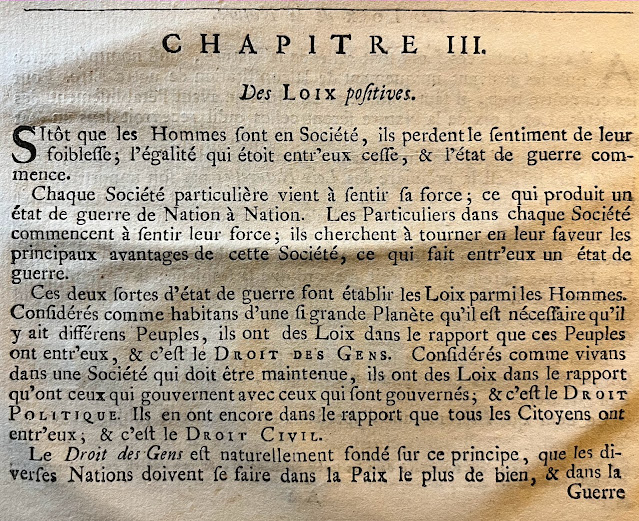

Let me offer one example - Montesquieu. In Chapter 3 of the opening Book, Montesquieu presents a fairly typical typology of the different categories of law, identifying the droit des gens (corresponding to the jus gentium or Völkerrecht - the law observed in common by all or most nations) and the droit civil (corresponding to the jus civile - the law enacted by a civitas such as Rome).

|

| Montesquieu, De L'Esprit des Loix (Amsterdam, 1749) p. 4 - an interesting edition I acquired last year, as it seems to have been published by the Dutch East India Company. Photo: Daniel Lee, 2023. |

One modern edition translates droit des gens and droit civil as 'the right of peoples' and 'civil right.' It might technically be correct, and could even be argued that such rendering is a matter of interpretive license. But it's clearly inaccurate. In passages like this (which were quite common in the law textbooks of the Enlightenment), authors were merely following a standard division between jus gentium and jus civile in the Roman law. They are not talking about rights, let alone 'civil rights.'

This has become a far-too-common problem in English-language scholarship. Hegel's Rechtsphilosophie is conventionally 'philosophy of right' (when it really should be 'legal philosophy'). Kant's Rechtslehre is rendered 'Doctrine of Right' (when it really should be just 'legal theory').

And what about this work:

|

| My 1646 Amsterdam Grotius. Photo: Daniel Lee, 2023. |

A popular translation that is still used by scholars and students describes this as a work on the 'Rights of War and Peace.' But it is clearly based on the model of the classical jus belli - the law of war.

All this is to say that I've become very distrustful of modern translations (and scholarship that relies on translations without consulting original sources). But this has also given me an opportunity to revisit familiar texts with a fresh eye. Is there anything new to discover in an (almost) 400 year old text like Grotius? It turns out, everything. At least that is what I've discovered as I began to consult the original source, and I have found it empowering - it cuts through the bullshit of generations of faulty interpretations and readings.

Anyway, what I think I'll do in the next few posts to get started is introduce some of my acquisitions. Perhaps Grotius might be an obvious place to begin.