Pufendorf

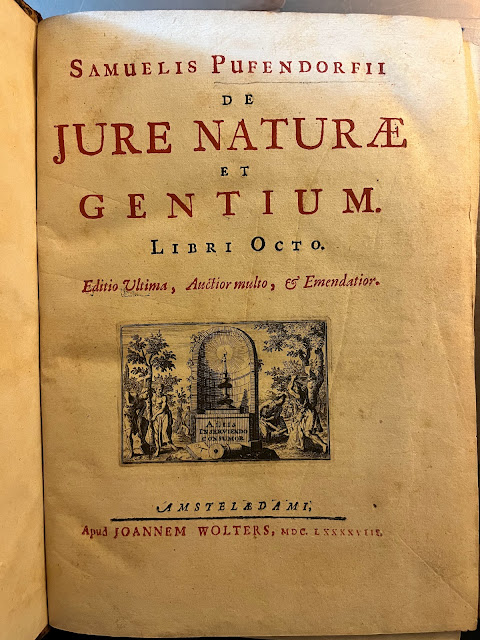

These are my two personal copies of Pufendorf - in Latin:

|

| Photo: Daniel Lee, 2023. |

|

| Photo: Daniel Lee, 2023. |

Political theorists now typically remember him for his contributions to international law and the social contract tradition. But he was so much more. Pufendorf is a figure of huge importance in the history of Western moral philosophy and economic thought. He is the most important theorist of law and ethics of the Enlightenment before Kant. Unfortunately the presentation of his writing was very technical and inaccessible to the lay reader without some specialized knowledge of Roman law. It's a real shame, though, because it is a very creative work and very satisfying to read how he synthesizes his different sources, from history, literature, philosophy, theology, as well as law.

I'll have more to say about Pufendorf, as I write more about him in the coming months. But since I was just talking about the 'Hohfeldian moments' in Grotius, I might make a similar observation in Pufendorf as well. Grotius anticipates the basic Hohfeldian distinction between liberty-rights and claim-rights in his treatment of jus and jus stricte dictum.

So does Pufendorf.

|

| Pufendorf, De Jure Naturae et Gentium (Amsterdam, 1698) p. 263, III, 5, §3. |